- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

The FUTURE IS LATINX

October 8 - December 2, 2020, Eastern Art Gallery

March 15 - May 9, 2021, Schiltkamp Gallery, Clark University, MA (under the title Latin + American)

August 30 - October 1, 2021, Three Rivers Community College, Norwich, CT.

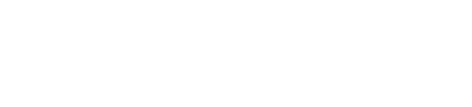

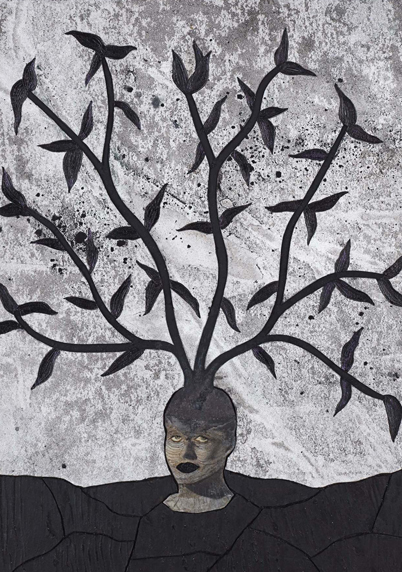

The FUTURE IS LATINX brings together fifteen exceptionally talented and critically engaged artists who challenge the myths that belittle their Latin American roots, unpack narratives of immigration twisted by politicians and media, and allow us to see a true reflection of their lives and dreams. They come from Connecticut and across North America, and represent a diversity of genders, racial backgrounds, and personal identifications. They address issues of systemic inequality, race, criminalization of immigration, and the disproportionate impact of the global pandemic on Latinx and other BIPOC populations. They also make our hearts sing!

The FUTURE IS LATINX draws attention to the rich cultural production of our Latino population as we continue on our path to becoming a “minority white” nation. In 2045, Whites will comprise 49.7 percent of the population, with 24.6 % Hispanic, and 13.1 % Black. Latinx will provide a majority of the growth in the nation’s youth and working age population, its voters, and its consumers, into the future. Statistic shows that Latinx is a popular term in high schools. Latinx looks to the future as it subverts the gender binary of the Spanish language.[1] Luis Alberto Urrea describes Latina/o/x as “a code-switching, culture-switching between street culture, Spanish, Spanglish, scholarly culture, poverty culture, Catholicism, shamanism, progressive politics, literacy, anger sharp enough to turn unexpectedly and slice.” [2] This community will dramatically change our politics, media, education, and cultural landscape. This is the future our exhibition anticipates.

The path forward will be challenging. An aging white population will not easily let go their majoritarian privileges. Currently, Latinx are severely under-represented on the faculties of Higher Education and in business, but are disproportionately represented in the prison population. They are variously marginalized by virtue of their color (not white enough; brown; Black) class position, or level of assimilation into “American” culture. [3]

The term Latinx has been is use since about 2004 to embrace populations living in the US identified as having roots in the Spanish speaking Caribbean, as well as Mexico, Central, and South America.[4] Latinx began as a gender-fluid term. It is a self-identification; many artists embrace it, some don’t, and some claim other, unique identities. Arlene Davila, the founder of The Latinx project at NYU, calls Latinx a slippery terrain that chases inclusivity, while warning us to not generalize about who they are and how and when they arrived here. Davila, along with Melissa Castillo Planas, professor of Latin-American literature at Lehman College, and many other watchful scholars, have made me aware of the urgent need for research, dialog, and exhibitions that would celebrate the value and complexity of those that may be gathered together as Latinx artists.

I use the term LATINX to introduce this conversation at Eastern as the university enters its new chapter of a diversity struggle – led by our campus chapters of the NAACP and Freedom Presidents – to serve our students of color (36%). The FUTURE IS LATINX is our first attempt to introduce the visual language of Latinx artists in an affirmation of their unique culture, and their quest for recognition and equality. It will be a source of inspiration for our minority students as they claim and define their own futures. Based in Windham, with its 40% Latinx population, we are especially committed to celebrating the multitude of Latinx identities. We are committed to welcoming immigrants and migrants and oppose current policies and commentators who seek to demonize both “newcomers” and longtime citizens.[5]

Although some are relative newcomers, many Latinx peoples have ancestry that predates the founding of the United States. The earliest groupings of Latinx artists settled in the Southwest — along the U.S.- Mexico border and Southern California – in the 1900s. They came to be known as Chicanos and, in the 1960s and 1970s, began to demand political power and affirm their ethnic solidarity and pride of Indigenous descent. At the same time, as Gloria Anzaldúa wrote about the border, it was a bleeding wound that starts from her birthplace of El Paso and continues as a 1,950-mile-long scar. Her words reminded me – born in Soviet Russia – of the Berlin Wall, which was much shorter but, in similar fashion, disfigured people’s lives, history, and culture.[6] Anzaldua’s visceral language, which freestyles across identities, symbols, and gods from various pantheons, evokes the unique resilience and lushness of today’s West Coast Latinx (Chicano) arts community.[7] It is for this reason that her poem Borderlands / La Frontera adorns the pages of our exhibition catalog. The poem is illustrated by Esteban Ramón Pérez, who grew up in the Los Angeles area. Perez celebrates the enduring inspiration of Anzaldúa for many of the artists in our exhibit.

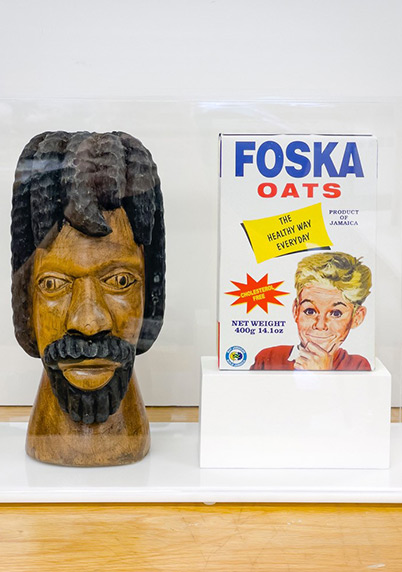

If Chicanos have been dismissed as illegals hopping borders, Puerto Ricans, have been marginalized on the basis of their colonial status as a US territory. They are “invisible” in both the US and Latin American art worlds, irrespective of whether they reside on the island or in the diaspora. As a colony, they are largely bypassed by the nation-centric focus of Latin American art, while in the United States they do not count as “American” artists.[8] David Antonio Cruz comments on this status: “You are always shafted, we become this hybrid and they don’t acknowledge our authentic Latin experience anywhere.” In his exquisitely rendered paintings of queer bodies, Cruz resists this erasure by arranging his subjects into compositions reminiscent of icons of Christian art. Resembling the Pieta and Trinity, his life size bodies reinstate the sense of dignity and beauty that their many marginalizations have subjected them to. Cruz relates that art was a safe haven, “it was just a way for me to create a place for myself.”[9] Cruz introduces symbols, masquerade, guilty pleasures, and playfulness to articulate this zone of safety.

It is not surprising that the majority of The FUTURE IS LATINX artists reside in NYC. It is a center of Latinidad.[10] The city contains both historical communities (Nuyoricans from the 1960s, Haitians, West Indians from the 1900s)[11] and transplants from all over the US that have come here to study, work, or insert themselves into these pre-existing artistic communities, or to create their own. [12] Dominicanyorkers, Columbians, Salvadorans, MexiRicans, Blaxicans and the many other artists who identify as simply Queens-based Latinx, are the future of the creative community in NYC. Nevertheless, they are still considered to be a new immigration cohort (although their families sometimes represent three generations of life in New York city). They remain under the radar: the cliché image of Latinx as “ghetto, the Bronx, the lady who cleans your house,” asserts their historical racialization, and the status of “forever foreigners.” Their quest for visibility and recognition of Latinx art is the necessary task to which The FUTURE IS LATINX is dedicated.

This exhibition spotlights a group of professional artists schooled at Yale, Parsons and Columbia among other prestigious universities. Trained in the Western art historical discourse, they weave studies in gender, race and anthropology with their non-Anglo heritage. They urge us to diversify our institutions to prepare for the Latinx future. Their call for diversity echoes that of Black artists’ daily efforts. There is a joy and energy in their work that proclaims: “We are here, our voice matters!” [13]

In this year’s Triennale at El Museo del Barrio the artists assumed a vanguard role. They remind us that this country must reckon with the fact that Latinx are essential to its survival and to its splendor, and have been, for generations. “To be a Mexican artist working in the United States is to be living twice,” says Blanka Amezkua, artist and community educator. “We have creative means to express problems in greater clarity, to tease out the ramifications of the current calamities. We also can articulate a vision of a just and fair place beyond calamities. It’s a privilege I don’t take lightly.” Her vision of an equal and inclusive future is the message we wish to share with our students.

Latinx women, young people, L.G.T.B.Q., and Afro-Latinos, among others, are a rising political force. They have been considered marginal in Latinx politics, but are now redefining politics and who the political actors of the future will be. Tanya Aguiñiga, Blanka Amezkua, Alicia Grullón, Glendalys Medina, Natalia Nakazawa, Lina Puerta, Shellyne Rodriguez follow the long tradition of women artists by owning their power to care, support, and share joy. Together with Felipe Baeza, Lionel Cruet, David Antonio Cruz, Ramiro Gomez, Rafael Lozano- Hemmer, Esteban Ramón Pérez, Dante Migone-Ojeda, and Vick Quezada they all remind us to be grateful to the Latinx community: our future is in their caring hands.

Yulia Tikhonova, Coordinator Art Gallery and Museum Services, 2020.

[1] Mochkofsky, Graciela. Who Are You Calling Latinx? The New Yorker, September 5, 2020 https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/who-are-you-calling-latinx

[2] Luis Alberto Urrea, A Rascuache Prayer, Reflections on Juan Felipe Herrera, my homeboy laureate. Poetry Foundation, September 2020 https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/154196/a-rascuache-prayer

[3] Méndez Elizabeth Berry and Ramírez Mónica, How Latinos Can Win Culture War, September 2, 2020, The New York Times, Opinion https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/02/opinion/sunday/latinos-trump-election.html

[4] Latinx also includes those who have been here for generations and those born in Latin America but raised in the United States, so-called the 1,5 generation.

[5] Arlene Davila, Critics and Slippery Terrain of Latinx Art, Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture (2019) 1 (3): 96–100, University of California Press.

[6] Gloria Anzaldua is spokesperson for conceptual and geopolitical study of the border, Latinx theory and Chicanx literature.

[7] Melissa Castillo Planas, A Mexican State of Mind. New York City and the New Borderlands of Culture, Rutgers University Press, New Jersey, 2020, p.24

[8] Arlene Davila, Latinx: Artists, Markets, and Politics, Duke University Press, NC, 2020, p. 37.

[9] David Antonio Cruz at Document Journal, 2019 https://www.documentjournal.com/2019/10/david-antonio-cruz-the-artist-giving-lgtbq-victims-of-violence-a-place-in-art-history/, accessed August 30, 2020.

[10] Latinidad was first adopted within US Latino studies by the sociologist Felix Padilla in his 1985 study of Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in Chicago, and has since been used by a wide range of scholars as a way to speak of Latino/a communities and cultural practices outside a strictly Latin American context. For more nuanced understanding of this term read Miguel Salazar’s The Problem With Latinidad The Nation, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/hispanic-heritage-month-latinidad/

[11] Nuyorican artists have settled in NYC from the late 1960s and early 1970s in Loisaida, East Harlem, and worked to validate Puerto Rican experience in the United States, who suffered from marginalization, ostracism, and discrimination.

[12] Arlene Davila has founded The LATINX project at NYU, that is dedicated to very unique experience, owning to its unmatched diversity, economic and artistic prosperity. Of the city’s ten largest immigrant groups that include other Latin American destinations (Ecuadorians, Colombians, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans) Mexicans (whose population raised post 9/11 have the highest rate of employment and are more likely to hold a job than New York’s native-born population.

[13] This September, The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) has hired its first senior director of belonging and inclusion, Rosa Rodriguez-Williams, who was a director of Northwestern University Latinx Student Cultural Center in response to the incident that led to accusations of racial bias in May 2019.