- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

Mushrooms as building materials

Biology researchers investigate new technology

Written by Katie Gaspar

Published on August 12, 2025

Mushrooms — you see them in the woods, put them on salads, and inadvertently grow them on old bread. Soon, you could be living in them.

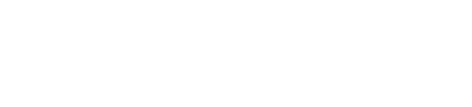

Mycelial bio-blocks are building materials grown with root strands of fungi. The material is strong, renewable, and biodegradable, and being studied at Eastern Connecticut State University. Senior biology major Derek Davis explored this new technology in an independent study with biology Professor Jonathan Hulvey this past spring.

To make the blocks, the two researchers elected to use Trametes versicolor, a fungus commonly known as “turkey tail,” due to its resemblance to a tom’s brightly colored feathers. The turkey tail is a common, densely structured fungus, a fine choice for a building material.

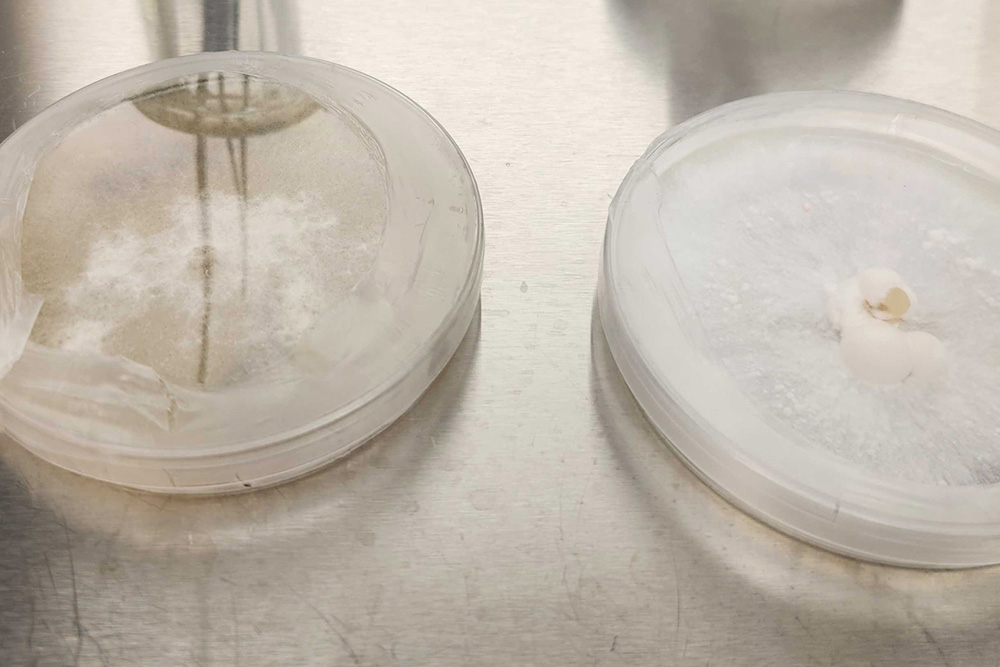

In classic laboratory fashion, Davis and Hulvey broke out the Petri dishes and began culturing and growing their samples. Then, inspiration struck. During their experimentation, Hulvey found an article about peroxidase, a molecule that helps break down a sterilizing chemical known as hydrogen peroxide.

According to the article, turkey tail’s mycelium — the vegetative part of the fungus, consisting of a network of branching, thread-like “hyphae” — should release enzymes, like peroxidase, in the area surrounding the hyphae. This would allow the turkey tail to grow while keeping out potential contaminants, like other fungi or bacteria.

After testing five samples with differing levels of hydrogen peroxide, they found that the fungi grown in higher amounts of hydrogen peroxide grew more quickly, an observation they implemented in phase two of their study.

“We switched to making the bio-block using wood chips and hot water in a bag,” said Davis. “We mixed it up, dumped some hydrogen peroxide in, added mushroom cultures to it, then allowed them a few weeks to grow.”

The mycelium snakes its way through the blocky mold, using the wood chips as food. It grows dense and thick, and, once the block is done, makes for an excellent building material, according to the researchers.

Davis and Hulvey decided to put their blocks to the test: how much pressure could they stand? Their first block was weaker, beginning to crack after about 50 pounds. Their second block, however, held up no problem. Asking their lab tech to stand on it, they found that this meager lump of wood scraps and mushroom bore the weight of a fully grown man.

Companies producing bio-blocks for construction use industrial presses to compress and heat their bricks, making them as strong as concrete, if not stronger, according to Hulvey. But buildings aren’t the only thing mushrooms are good for. Organizations around the world are joining the mycelial movement, innovating new uses for fungi including biodegradable packaging materials, synthetic leathers, vegan bacon, batteries, and more.

However, what’s grabbing Davis and Hulvey’s eyes most is the question of mushrooms in space. “NASA has been doing research, looking at the potential to use these mycelium building materials to construct structures on Mars or on other planets,” said Hulvey.

For future research, Hulvey and Davis are looking to apply for grant funding from NASA, with the idea of testing different fungi species to use in bio-blocks. Might different mushrooms work better for different uses, or in different environments?

As mushroom technology spreads like spores on the wind, Hulvey and Davis optimistically look forward to a fungi-filled future.