- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

Prison Arts exhibit opens with artwork that ‘transcends’ prison

Written by Lucinda Weiss

Published on March 21, 2023

“Pandemiculous,” by Damian Campanella, colored pencil on paper, is one of the artworks being shown.

More than 350 works from 100 artists are being exhibited in the 43rd annual Prison Arts Show at Eastern Connecticut State University’s Art Gallery from March 20 to April 22. It is the largest prison art show in the country, according to Jeffrey Greene, director of the Community Partners in Action’s Prison Arts Program.

The artworks range from large-scale sculptures to drawings and are the work of current and former prisoners, including inmates at the state’s only women’s prison, York Correctional Institution in Niantic.

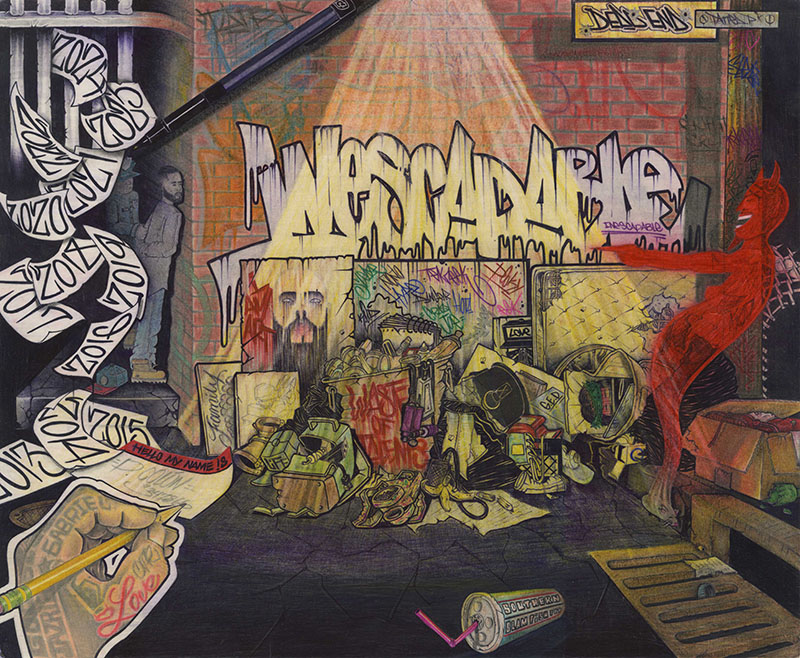

“Waste of Talents,” by Pedro Colon, colored pencil and pencil on paper

But the show “isn’t about prison art – it’s about transcending the prison,” said Greene. Prison subdues individuality, and “this is a program that gets people to really figure out who they are,” he said.

One of the large sculptures on display has two reclaimed conduit-wire-and-wood arms reaching for each other through a gallery window. Created by Danny Killon, a former prisoner, they are about communication, Killon said. “Art is a language – it’s what Jeff facilitates.”

Killon left prison in 2007. “Since then, my whole life is about art,” he said. While in prison, he participated in the Prison Arts Program for 10 years. He now owns a gallery in Troy, N.Y., clled Weathered Wood, where he sells furniture he has made from reclaimed wood.

“This program literally saved my life,” said Killon, who only “tinkered” with art before he went to prison.

“Wow,” by Mark Francis, colored pencil on paper

Another alumnus of the program, Ray Materson, has exhibited his work in Paris, Slovakia and Great Britain, as well as at the American Museum of Folk Art in New York. While in prison, he unraveled socks, using the thread to stitch miniature tapestries.

The Prison Arts Program runs art workshops in five prisons around the state and has a waiting list of inmates who want to participate. Greene, who teaches the workshops, gives practical advice on how to manage art projects in prison, and he teaches the technical aspects of shade, line and perspective as they come up.

The prisoners keep their artwork in their five-by-eight-foot cells, shared with another prisoner, and they often use “trash can” materials -- toilet paper for papier-mâché, used soap bars and parts of buffing pads. Under prison policies, the artwork is considered “contraband,” even though the program is permitted. This means it can be confiscated at any time, so the artists “learn to be respectful, because you don’t want your work destroyed,” Greene said.

They also learn to empathize with other people, he said. “You become more connected to the community than when you were on the outside.”

The program encourages people to take action that changes their life and the life of the prison, Greene said. “They realize they’re part of something much larger than the prison.”

“The Church of the Angels,” by James D.E. Scott, sculpture

The poster art for the exhibit shows James D.E. Scott’s “The Church of the Angels,” a sculpture made with 100 pounds of soap, toilet paper, buffing pads and acrylic paint, among other materials. Scott has other installations at the program’s permanent exhibit at the historic Old New Gate Prison. Greene once visited Scott when he was in solitary confinement, where he had made sculptures of trees out of toilet paper and stuck them to the wall.

“This is a guy who can’t help but make art,” he said.

Only a few women are represented in the show because the program has been slow to re-start at York prison after COVID. Some exhibitors have contributed to the annual show for decades, and others are new.

Greene, who has directed the program for 32 years, said his goal is to make sure the participants are not defined by the confines of prison.

“This is a project that makes them more human,” he said.