- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

Scorpion stinger could be source of new antibiotics

Discovery could aid in fight against antimicrobial resistance

Written by Michael Rouleau

Published on January 17, 2023

New biology research at Eastern Connecticut State University has discovered that novel bacteria exist in the stingers of scorpions. Long considered a sterile environment, the research finds for the first time that this venom-producing appendage in fact contains a diverse microbiome that may aid in the development of new antibiotic medicines, which could help alleviate the global issue of antibiotic resistance.

The research published this January in the peer-reviewed scientific journal PLOS One, and is titled "A first molecular characterization of the scorpion telson microbiota of Hadrurus arizonensis and Smeringurus mesaensis."

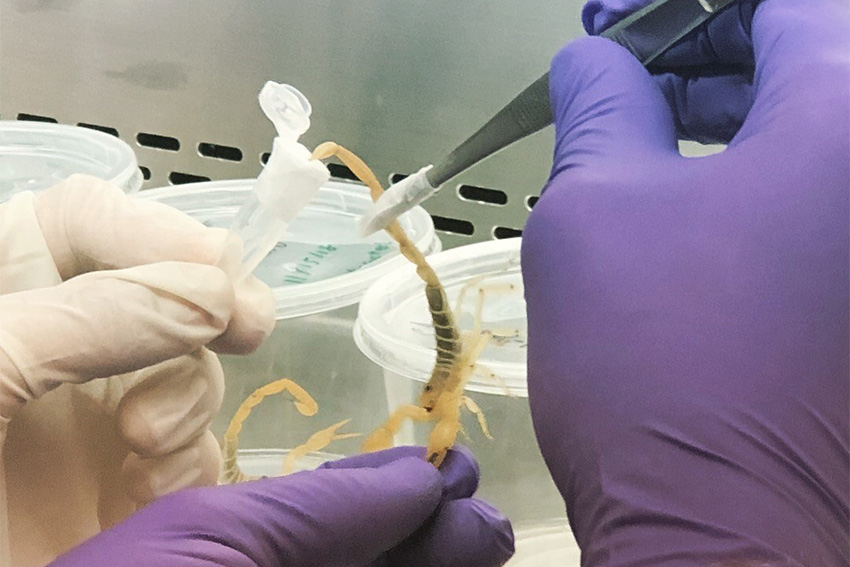

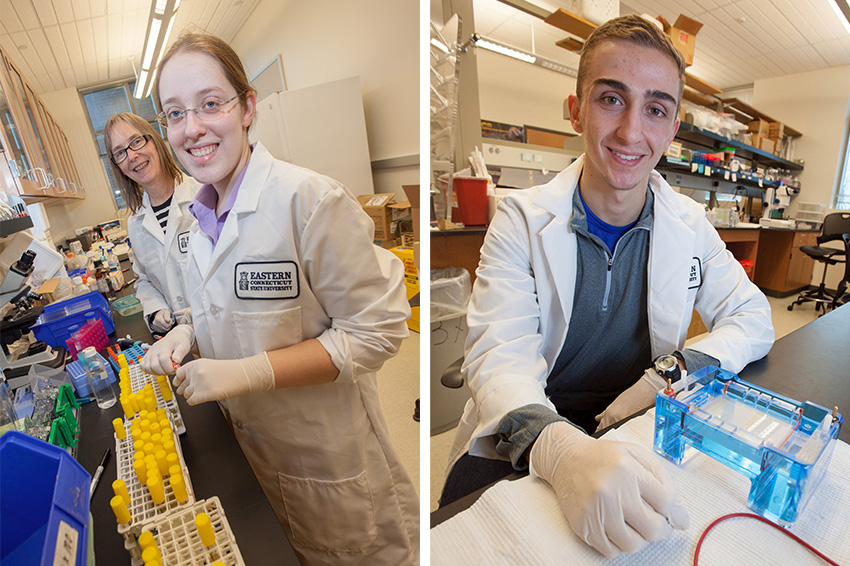

“The research shows that scorpions contain vast types of bacteria in their venom-producing organ, the telson,” said biology Professor Barbara Murdoch, who conducted the research alongside Professor Matthew Graham and former biology students Christopher Shimwell ’20 and Lauren Atkinson ’19. “This contradicts central dogma, since the telson has been previously thought to be a sterile environment, devoid of bacteria.”

Scorpions represent an ancient lineage of arachnids that have permeated throughout the world and are incredibly resilient. Given the harsh environments that many scorpions live in, scientists have speculated about the organism’s microbiome in its evolutionary success.

“Little is known about scorpion microbiomes, and what is known concentrates on the gut,” explains the paper’s abstract. “The microbiome is not limited to the gut, rather it can be found within tissues, fluids and on external surfaces.”

“We were curious to see if the stingers of scorpions, an incredibly old group with origins in the Ordovician (more than 440 million years ago), possessed unique bacteria adapted to these ancient venomous environments,” said Graham.

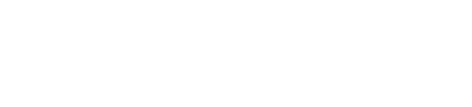

To do so, the researchers isolated telson DNA from two scorpion species from the American Southwest—the Giant Sand Scorpion and the Desert Hairy Scorpion—and identified the collection of bacteria present. The results confirmed that the telsons indeed contain bacteria, that each of the two scorpion species possessed unique combinations of bacteria, and that some of the bacteria represent new lineages.

“We hypothesize that some of these bacteria may contribute to the immune function of the scorpion or the venom’s toxicity,” said Graham, “which may change the way we view the biology of scorpions and envenomation by their stings.”

The study’s greater implications concern the global health crisis of antibiotic resistance, in which drugs meant to treat bacterial infections are becoming increasingly ineffective at killing bacteria. Combatting antibiotic resistance is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

“Although most people don’t care about scorpions,” said Murdoch, “finding novel bacteria within scorpions may lead to new sources of antibiotics to treat human microbial infections.”

Funding for this research came from a grant by the NASA Connecticut Space Grant Consortium in December 2017. The project was completed in 2022. Visit PLOS One's website to read the article online.