- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

The Roots of Haitian Migration

Written by Dwight Bachman

Published on February 12, 2020

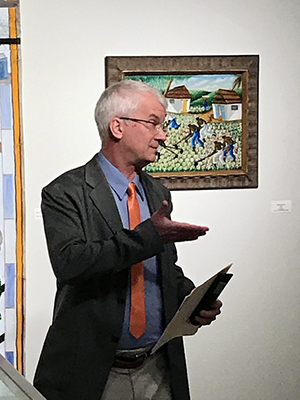

Darrell Irwin, visiting assistant professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut, gave a lecture on “The Roots of Haitian Migration” in Eastern Connecticut State University’s Art Gallery on Feb. 10. Nicolas Simon, assistant professor of sociology at Eastern, collaborated with Irwin on the talk.

Irwin’s lecture complemented the current “Creating Dangerously: Art and Revolution” exhibition on display at the Art Gallery through March 12. Irwin used a rich photo archive of the lives of Haitian farmworkers — taken by renowned photographer Arthur Bacon — to provide a visual context for his talk.

Irwin began researching Haitian immigration in the ’80s for the Florida Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services after graduating from the University of Florida. He was assigned to the town of Belle Grade, FL, a farm community located on Lake Okeechobee.

Though only 40 miles from the polo fields and malls of West Palm Beach, Belle Grade was known nationally for its high rate of poverty and considered by authorities to be the poorest town in America. He recalled that he often had to create new Americanized names for many of the 20,000 illiterate Haitian immigrants upon their arrival.

Irwin said Belle Glades has seen many waves of immigrants directly linked to the area’s agricultural industry. In 1958, before the Castro regime in Cuba, cheap Jamaican migrant labor harvested 47,000 acres of sugarcane in Florida. By the 1964–65 season, the number of acres reached 228,000 acres. Belle Glade set several world records for sugar production from 1959 to 1962. Irwin said Haitian immigrants took over the sugar cane jobs and worked hard to establish themselves in Belle Grade. After the Cuban revolution, many of Florida’s farmers who grew fruits and vegetables received incentives from the U.S. government to convert to sugarcane.

At the same time, on the other side of the Lake Okeechobee, in Immokalee, Mexicans cultivated and harvested tomatoes and other vegetables. Irwin said many Mexican farmworkers still live in rotting shacks or dilapidated, rat-infested trailers in Immokalee, 30 miles inland from affluent Gulf Coast resorts. Progress takes place slowly — in 2014, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers managed to forged partnerships with giant restaurant companies like McDonald’s and Taco Bell to improve conditions in the fields.