- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

Published on July 13, 2021

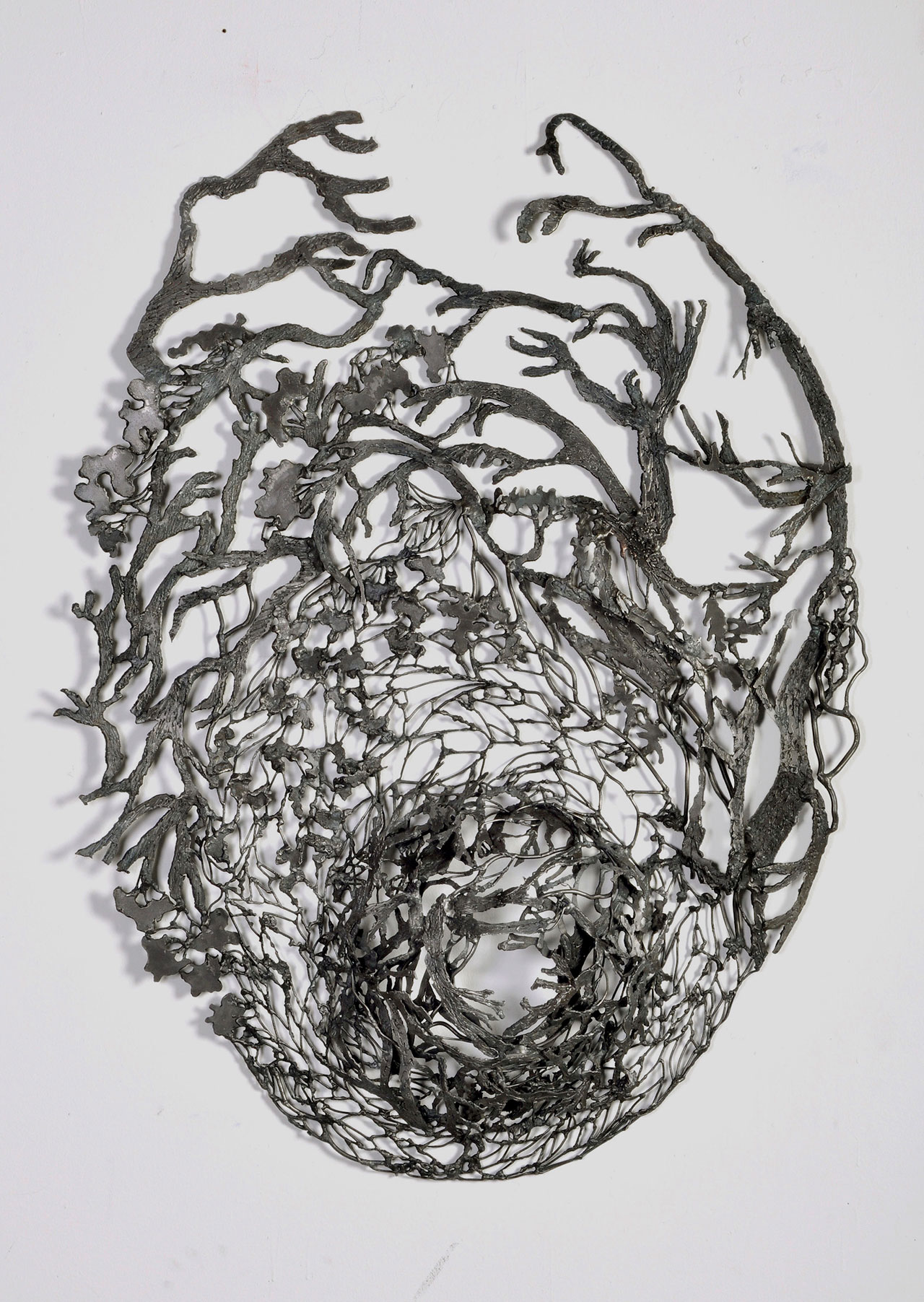

Roya Farassat

I made my metal sculpture in two different places. Initially before the sculpture center became a museum in Long Island City, it was The Clay Club, founded by a sculptor providing a platform for sculptors to make work. It was located in a Carriage house on East 69th Street in Manhattan. Sculptors like myself welded and carved stone and made clay work. My welding work continued there for a couple of years until they sold the building and became a sculpture museum in Long Island City. Then I moved my practice to Educational Alliance, originally a settlement house for Eastern European Jews in Lower East Side. I welded there until 2011 until their mission changed and they got rid of their welding department.

***

There is definitely a connection between my metal sculptures that draws inspiration from shapes of objects that were used traditionally in the Safavid period such as spherical ornaments, metal ewers, kettles, wine bowls, inkwells and silver inlaid jugs.

As a small figured woman it intrigued me to work with a medium that was considered to be a specific male gender job. During the time that I was welding I was very much drawn to the work of sculptor, Giacometti. His roughened surfaces and attenuated forms were reduced to the bare essential. Like him, I had a lot of existential questions and became interested in the human condition and the human behavior while trying to figure out my own conflicted identity. Issues relating to aging, loss and unpredictability became themes that I wanted to explore. The dark grey color of metal was attractive to me and its hard surface spoke to me in volumes about something no longer living. I found myself identifying with the metal, steel, because it was tenacious, yet malleable when heated and hammered into a new shape.

***

“A Day After Tomorrow”#1, is a metal wall installation that was inspired by the curvilinear central medallion design in Persian carpets. It contains individually cut pieces of steel in the shape of leaves and branches. This repeated lace like patterns are welded together in a circular motion that expand flatly on the edges of the wall and contract in the center in the shape of a belly. The circular movement gives a feeling of continuity and and for me symbolizes a renewal of life.

As artists living in diaspora, we have been asked numerous times about our conflicted identity. When I was younger, it felt imperative to claim an identity, but now that I’ve lived most of my life outside of my native country, I no longer feel the need to solidify it. In fact I find that claiming my past identity is extremely isolating and preventative in reinventing myself. The recent Covid-19 pandemic took millions of lives and established that there’s nothing exclusive about us. We are only as unique as we want to appear, but in reality everything that presents itself as original has really derived from something else. In a small setting, my physical characteristics may be the only thing different about me, but declaring it as something distinct, feels very superficial. I believe we can choose our inherited culture or abandon it for a new one. For me, it’s nothing personal; it’s a choice.

Now to be included in an all women Iranian exhibition seems to be contradictory to all that I’ve stated. I’ve agreed to it, but does that make my work Iranian and is it apparent that a woman made it? I can only laugh, and it’s venomous. - Roya Farassat