- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

Published on December 11, 2019

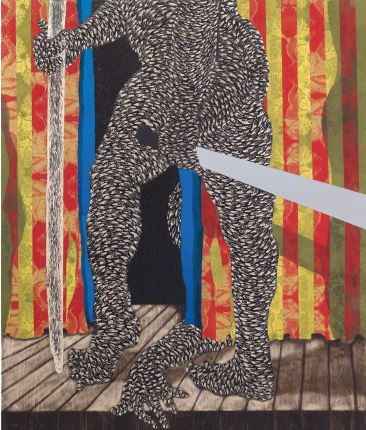

Didier William

Didier William

DIDIER WILLIAM paints silhouette figures composed of all-over fields of small eyes incised into the picture plane and inked in black. The tiny machetes that form the surface pattern allude to the heroines of the Haitian Revolution. They remind us of the phantoms born of untold violence. The eyes are a Voodoo symbol and give the figures a spooky power. Not content to settle into a role as “object” of our gaze, William’s figures stare back at us with eyes like ghosts in a haunted forest. They serve as an analogy for the arduous labor of Black re-imagining in the fight against a white hegemony. William pays homage to contemporaries like Mickalene Thomas and the colorful fabrics of West Africa.

Duval Carrié, Charlier, Huber, Smith, and Williams experiment with diverse forms, media, and artistic traditions. They create a powerful tension between established artistic genres (painting, portraiture, installation), formal artistic styles (conceptual and realist), and discursive modes of creative production (collage, assemblage). Their work differs from those more traditional paintings by Haitian artists from Eastern’s art collection. However, it is the traditional artists who preserved the spirit of cultural freedom, seeded by the revolution. Our contemporary artists are heir to this freedom. The danger of their art is rooted in the never ending struggle for dignity.

How should we understand the dangers these artists face? Exclusion and misinterpretation are a threat that faces every artist. Haiti has been portrayed as a land of savages. Columbus described it as an island of cannibals. Its heat and humidity, tropical food, and diseases, have had detrimental effects on inhabitants and predisposed them to moral turpitude, brutality, sexual laxness, and insanity. Here, the African gods made a pact with the devil to conjure up Voodoo, the religion of the revolution. Voodoo has been blamed for every possible disaster, natural and human-made, including AIDS, debt, deforestation, corruption, exploitation and violence. This region has been considered an antipode to Western rationalism, historical progress, and the Enlightenment – a black hole of “otherness,” in which the colonialists defined their superiority.

I am reminded of Stuart Hall’s assertion that the colonial discourse was fueled by the desire for otherness and its dichotomies of civilized/uncivilized, cultural/ natural, superior/inferior defined in this region. These linkages between coloniality and “otherness” had a formative impact on the visual arts of the Caribbean. The multivocal local art could be grouped into two schools. The first group employs the raw art objects that served in Voodoo ceremonies. The artists transformed readymade and recycled materials into apocalyptic images. Their sculptures render the barbarian, naïve, and occult. The second school is refined and peaceful. These are the detailed paintings of rural areas and the towns and their central squares, perhaps made for tourists and a secular environment, that are displayed in our exhibition.

Haiti was not alone, doomed as a signifier of “otherness.” The entire Caribbean constellations of islands: were suspicious tabula rasa. Each island was a vulnerable rim opening onto the sea, where the tensions between movement and settlement, island and mainland, land and water were defining parameters. Antonio Benítez-Rojo, an acclaimed Cuban novelist saw similarities between archipelagos world-wide, including New Zealand and China. While individual islands maintain their uniqueness, the connections between seemingly disparate cultural elements constitute one culture.

In the case of Haiti, the island has been an authentic cultural crucible, the mix of Carib, Arawak/Taino Indians, the Spanish invaders, the fearsome Brothers of the Coast, filibusters, pirates of all kinds from French, English and more than thirty African tribes. Caribbean-ing is a global condition. The artists in Creating Dangerously utilize local , but they speak about freedom struggles across the globe.

Indeed, the Caribbean is a part of the Black Atlantic: the continents of Africa, South and North America and Europe which has been shaped and sustained by the slave trade. Between 1492 and 1820 millions of African people crossed the Atlantic. Haiti was one of the ports through which the “insemination of the Caribbean womb with the blood of Africa” took place. This violently brutal migration played a key role in the call for freedom that was rooted in African heritage. In the words of Natalio Galan, the ancient pulsations brought

by the African diaspora, the memory of sacred drums and the words of the griot were amplified by the rhythms of the sugar mill machines, the machete strokes that cut the cane, the overseer’s lash and the planter’s language that awoke the spirit of freedom.

The 1791 Haitian revolution posed a set of absolutely central political questions. As Laurent Dubois states, Haitian revolutionaries were survivors of the Middle Passage and carried over the African spirit of independence. In her book, Haiti, Hegel and Universal History Susan Buck Morss claims that the “Haitian revolution informed the Hegelian master/slave dialectic and that it stands above the French and American revolutions.”

It inspired the abolitionists, the Civil Rights movement, and the Black Lives Matter movement. This revolutionary creativity imbues the artworks in Creating Dangerously. It also sends out danger signals to those who are in power.

The more traditional artists in our exhibit ironically – and no doubt intentionally – reveal the dangers that simmers just below the surface of their bucolic Haitian landscapes through their valiant attempts to hide it from view: Haiti as Paradise defies the reality visible to all!

Hector Hippolyte, Jacques Wesley, Wifrid Teleon, and Henry Valbrune depict idealized scenes of Haitian life, towns squares, rural villages, children rushing to school, and tropical landscapes. The pastoral scenes, bright palette and joyous spirit of the paintings could be viewed as politically safe style reinforced by the state, which conduced an intensive campaign against voodoo’s “superstitious beliefs,” in which tens of thousands of sacred voodoo objects were destroyed. These artists utilized multiple perspective, detailed rendering, vivid colors, and simplified human forms. These stylistic qualities stand in sharp contrast to the highly visible political stance of our contemporary artists.

Other Westerners took a stake in the development of Haitian culture, as they continued to search for their alter-ego – the exotic other. In the 1940s and ’50s Haiti was touched by the globalized spread of Modernism.

André Breton, Maya Deren and Wifredo Lam were drawn to Haiti in search of “raw” imagination untainted by Western culture. They championed its “unspoiled” nature, which led to the subsequent commodification of Haitian “primitive” art by Western collectors. The selection of paintings on view were gifted by local art patrons, Stanley Popiel and Ingrid Feddersen, who worked in Haiti on a health mission. Early scholars saw Haitian art as important evidence of an African diaspora aesthetic, and journalists described it as naïve and exotic.

Until recently, the artists in this exhibition were dismissed as “ethnographic:” conjured in isolation and under the mystical Voodoo spell. Latin American art historians often selectively excluded Caribbean artists, favoring the Hispanophone countries and omitting the French, Dutch, Anglophone and other islands. In the last decade, a new generation of scholars emerged. Tatiana Flores, Michelle Stephens, Jerry Philogene, and many others have suggested nuanced definitions of Caribbean identity, and placed it firmly within the Diasporic and Trans-Atlantic discourses.

Creating Dangerously humbly follows in their footsteps and attempts to reveal the almost invisible linkages between the mainland Haitian artists and their contemporary colleagues. The exhibition proposes a system of definitions that binds together the works on display into a close knit body of cross-cultural dialogs and traditional connections. It conveys the multiple vantage points that converge and articulate the diasporic Caribbean experience.

Creating Dangerously emphasizes the resilience of Haitian people, communicating their optimism and their commitment to the survival of their unique culture. They create in the dangerous context of escalating violence and anti-immigrant frenzy. Our only hope is the artists, whose voices refute the noxious policies of our politicians and the white noise of the media. They provide us with inventive tools with which to reflect on our collective histories. They challenge conventional ideas of art practices and explore the global realities of the Haitian artistic diaspora. They imagine freedom as it emerges from old conventions and stereotypes. Artists daily risk everything to create art that boldly guides us towards a more just and humane future.